“We’re Talking About Practice…”

I remember sitting in my apartment in Seattle with my dad in 1998. He was in the US for the World Shakuhachi Festival in Colorado, and I convinced him to stop in Seattle on his way home to go into the studio with me. We were having a bite to eat and watching my beloved Seattle Supersonics (RIP) play the hated LA Lakers. My dad loves sports, and as he watched the players glide from one end of the court to the other, he said I wish I had that kind of discipline. A very sobering thing to hear coming from a man who practiced every. waking. moment of his life.

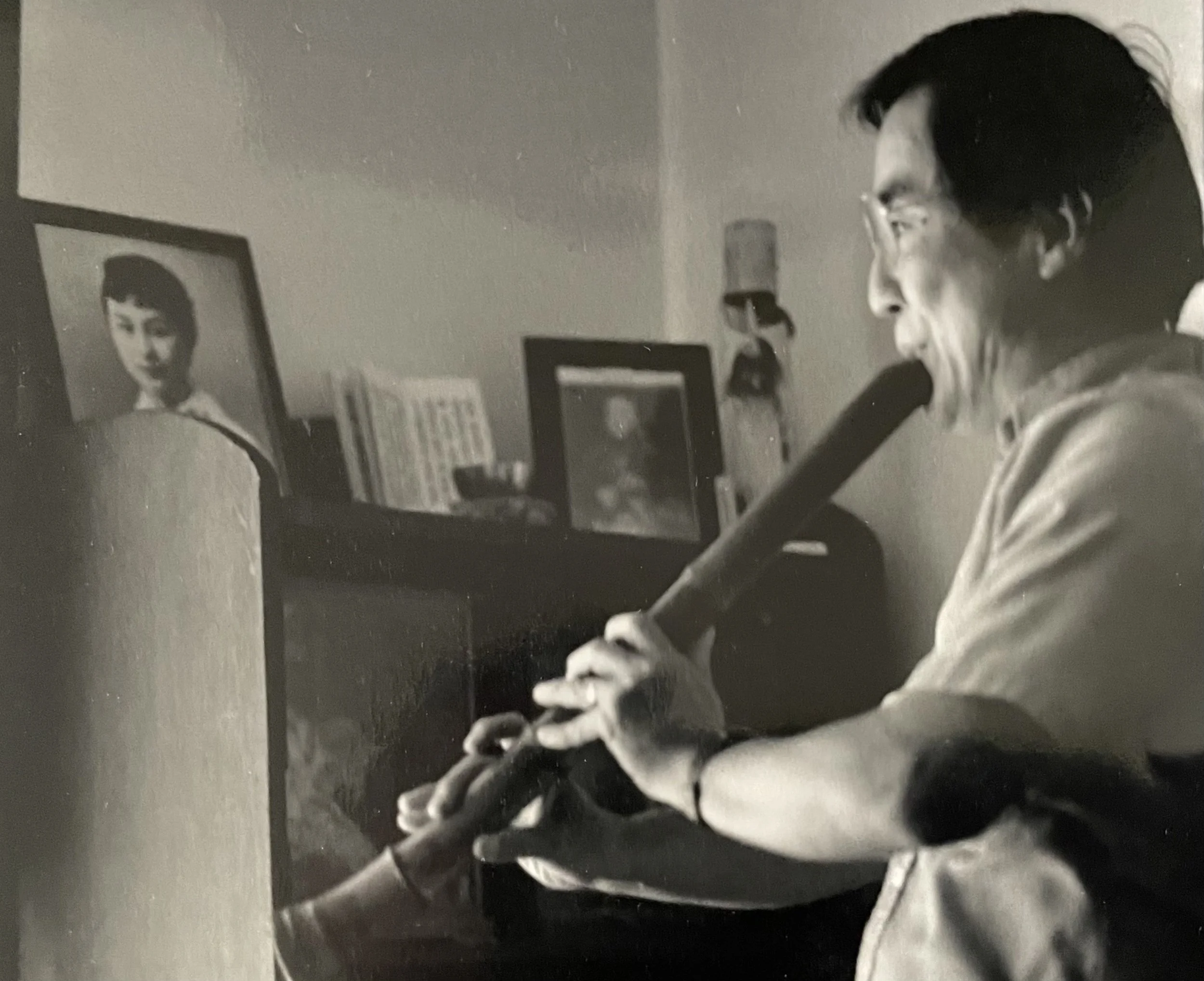

Seattle, 1988, likely watching the Mariners get slaughtered.

That’s not an exaggeration. For example, my dad would watch the sumo tournaments, starting with the juryo round and all the way through to the final makuuchi bout and play shakuhachi the entire time. Same for all nine innings of baseball (and in the case of extra innings, them too). He made a small exception for actual meals and a brief postprandial repose.

During our lessons, my dad didn’t necessarily spend a lot of time teaching me fundamentals, like proper breathing technique or embouchure; those came naturally for the most part as did fingering. Meanwhile, shakuhachi notation was intuitive to me in a way western notation never was. He set a furious pace, and my days were long. Although it was challenging, it was rewarding because a.) it was the first thing in my life I was at all good at, and b.) it was nice to spend time with my dad who to that point had been kind of aloof to put it mildly.

When he did speak about fundamentals it was brief and allegorical. Draw your breath not like you’re breathing into the bottoms of your feet, but like you’re drawing air up from the other side of the world. He also said that every note should be it’s own piece of music. That’s how he taught me to warm up. Play through the notes, but not just as a scale and more like a collection of different songs.

My father’s dear friend and colleague Inoue Shigeshi literally illustrated that for me. I sat across a table from him as he drew out the shakuhachi notes ro-tsu-re-chi-ri with a corresponding image of what he wanted his sound to evoke. Mr. Inoue was a few years my dad’s senior and a brilliant instrument maker. He was also a formidable musician but crippling stage fright limited his performing. I was a relatively quiet player. I still am, really. Mr. Inoue, however, was a force of nature—a huge sound. My dad sent me to him for lessons in the hopes he might open a door to more assertive playing. I had a great time playing with him but I think my somewhat restrained sound is hardwired into my operating system.

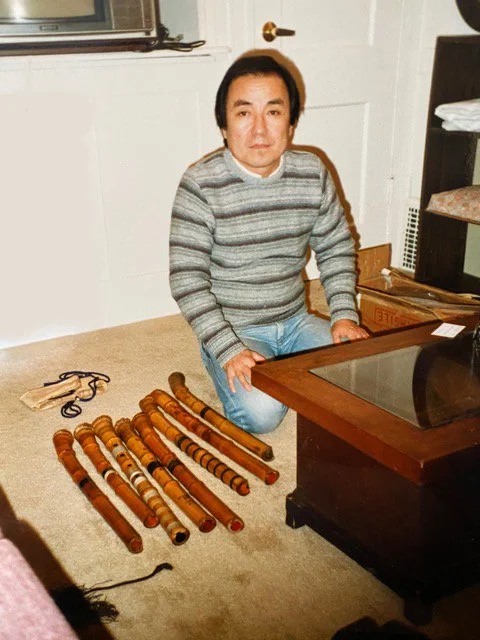

Inoue Shigeshi (with his insane dog, Lan), 1991

My dad would say you’ll never be 100% for a concert. Maybe it’s your nerves, maybe you had an argument that day, maybe you’re not feeling well, or are stressed about money, whatever. These distractions are constantly trying to worm their way into your mind; at best, you’ll be 80% of your actual ability, so practice with that in mind. Some small bit of uncertainty will balloon into a chasm of despair on stage.

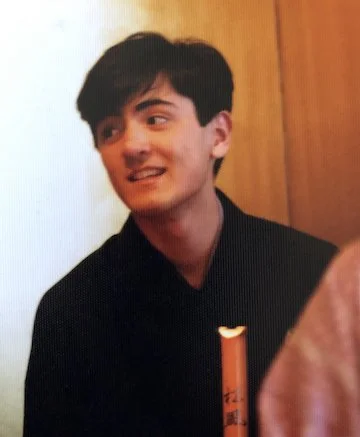

Takasaki, 1988

This is the face of someone who’s just been told the piece they’re about to play is not the one they practiced, and is in fact, one they’ve never heard.

He also said if I didn’t get nervous before a concert, then likely I didn’t care enough and I should find a different career. I always appreciated that because I have terrible stage fright and remembering that nerves aren’t a bad thing has been very helpful. For a short while, I employed a dubious self-talk stratagem saying things like, I’m not nervous… I’m excited! These days, I just go back to accepting my nerves as part of the process.

He told me that a working musician should consider themselves very lucky if they can make even a fraction of their income through live performing in concert halls or festivals. More often than not, the venues will be less than ideal. Most of what you’ll do is background music for people who actively ignore you at best—you’re hired help, and nothing more—or with open contempt. The vast majority of where you’ll put your energy is teaching, which isn’t a bad thing.

My view from 1988~1992

(photo courtesy of John Singer)

In spite of the somewhat grueling lesson schedule, my dad never lost patience with me, belittled me, or was cruel. To be fair, he also never once complimented me on my playing, but given his upbringing this was to be expected. I think back to that period of my life and the sheer number of hours my dad dedicated to my musicianship with amazement.

When I first came back to the states in 1992, many of the people who came to me for lessons weren’t looking to learn music per se, but were seeking an extension of their Buddhist practice; a spiritual guide. This made me uncomfortable at the time. I wasn’t able to reconcile the word spirituality with anything other than White, Conservative Christianity. At this stage, the spiritual nature of playing this music—any music—is obvious, but the 20-something me was brutally, unreasonably secular when it came to shakuhachi playing.

The greatest challenge for me as a teacher is finding ways to transmit things I learned through osmosis. I don’t have a this one weird trick will make you a master shakuhachi player in just 15 minutes a day! hack. But actually, it’s my favorite part of teaching. Everyone learns differently and it keeps every lesson new and interesting.

More anon,

Hanz