August, 1988

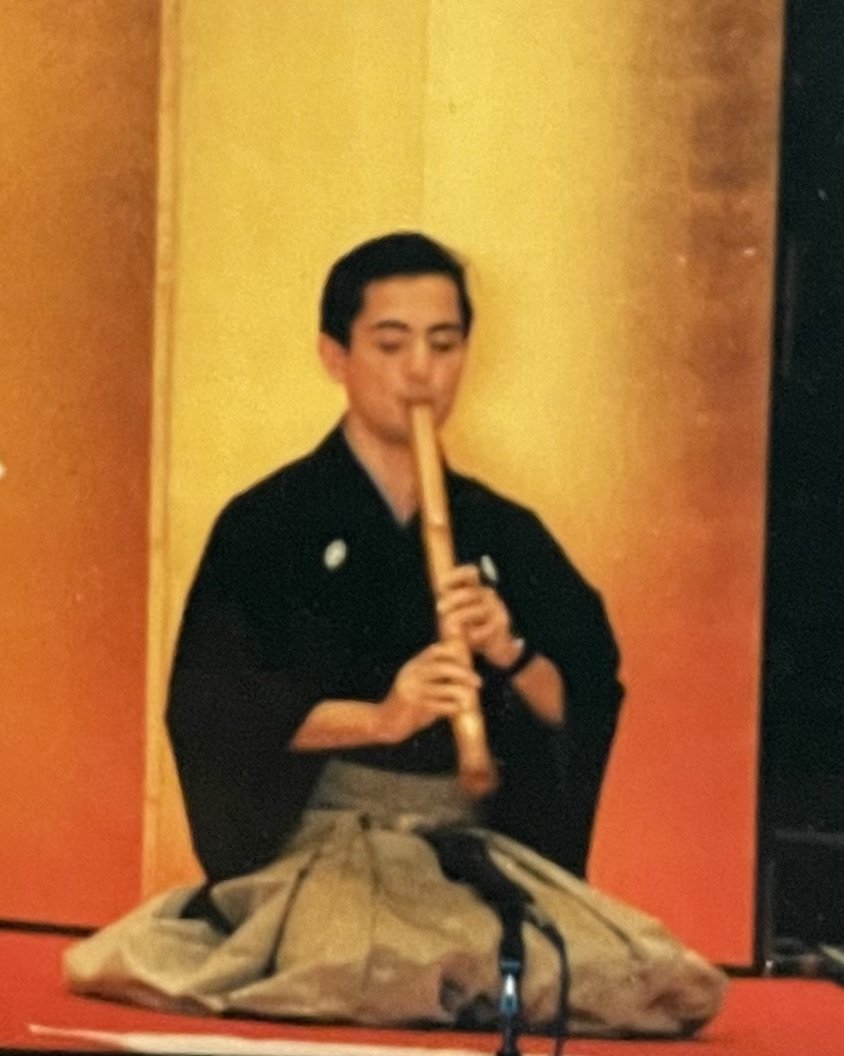

In telling my musical origin story, I make mention of the fact that I started playing in April of 1988 and debuted in August of that same year. It’s not a brag, or even a pat on the back: It’s simply how it went. My dad was happy that he could move quickly with me, and didn’t have to spend a lot of time—any time, really—on fundamentals like breathing or embouchure. Having me debut as quickly as possible was a good move for him given that he had been living outside of Japan for 25 years at that point. This concert was much less a debut for me as it was a declaration of his return; having me there established the continuation of the legacy.

My dad, in the green room

I had absolutely no performance experience, and I was completely unfamiliar with the concept of run of show. In Japan, hurry up and wait is less cliché and more of an art form. On show days, you arrive to the venue around 11 or 12, and you’re there pretty much until they lock the doors. Then there’s an afterparty. I didn’t know any different at the time so it wasn’t any hardship.

The concert was held in Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture, just across the water from Kyushu. My memory of it is simultaneously vague and luridly vivid. I was to play three pieces, all duets with my father, and I was nearly sick from stage fright. I was a total fish out of water; I didn’t speak any Japanese yet, and had never even once set foot on stage before for any reason.

It was my first time wearing kimono and hakama (the men’s trousers worn with formal Japanese attire) which at that time felt kind of like wearing a straight jacket. You start with the tabi (socks), then the jiban, the layer under the kimono, tied with a silk cord. I was a skinny eighteen year old, so I had to pad my waist with tenugui, long, narrow cotton towels in order to keep everything in place. Over that goes the actual kimono, tied with another plain silk cord, which had been made for me a month or so earlier and bears our family crest, then the obi.

my aunt Mieko with the assist

Each component is silk. The obi is a fairly heavy raw silk; mine was brown and flecked with orange. It has to be tied excruciatingly tight in order to stay in place. the knot in the back where you tie the obi creates a kind of shelf for the back panel of the hakama to rest on.

Once it’s on, the obi is almost completely covered by the hakama, which has an elaborate series of straps that first tie the front panel leaving just a sliver of your obi showing. The back panel then ties around the front in a tidy bow.

photo by KaizenNW

With every layer, I felt further constricted and bound. I was terrified that I would need to use the bathroom and have to go through the whole rigmarole again which magnified my anxiety, and of course made me feel like I really needed to use the bathroom.

Vaunted Japanese hospitality was utterly lost on me because even the thought of eating put me right over the edge. I also didn’t want to take in any fluids because I was so worried about needing to use the bathroom. So despite the lavish spread in the gakuya (green room) I abstained.

After what felt like an actual eternity, it was time to get on stage. I was to the left of my father, kneeling on the ground in traditional seiza, or kneeling position. Traditional music is performed this way on red felt with large gold screens as a backdrop. My dad quickly explained what was going to happen: We would bow until the curtain was all the way up, then we’d slowly raise out heads as the applause faded. The first piece we played, E Ten Raku, starts with a short solo line—first from my father, which I would repeat later in the piece—and I wasn’t to raise my instrument until he was on the last four beats of this intro.

The stage manager asked if we were ready. Yoroshiku onegaishimasu my father said to him; a sort of please-and-thank-you all rolled into one. As we bowed our heads, my dad said to me quietly, no mistakes. And the curtain went up. There was no going back.

I don’t remember the actual playing, but I think it went fairly well considering. We had practiced seemingly unendingly so I was comfortable with the music at least. Strangely, once I was on stage, in the seconds before the curtain went up, my nerves settled down for the most part aside from a slight tremor in my lower lip. Unfortunately, my three numbers were spread out over the course of the night giving my panic ample time to rise and fall like tidal waves, cresting at the moment before I knelt on stage, subsiding as the curtain rose, and starting all over again once the curtain fell.

I’ve spoken a bit about professional names here. That night I was given the name Baikyoku, which had been my grandfather’s name before he became Kodo IV. E Ten Raku is an arrangement of my grandfather’s as well. After the concert at the reception line in the lobby, many of my grandfather’s surviving students came to tell me—sometimes tearfully—how much I resembled him, how I played just like him. If I hadn’t been so scared out of my wits (and, you know, able to speak Japanese) it would’ve had a much greater impact on me. At the time, I just smiled an nodded. Looking back, so much of that concert was so beautifully scripted; a return for my father, a debut for me, and an homage to my grandfather.

Kodo IV

More anon,

Hanz