A Song of Plovers

photo by Colm MacCárthaigh

Recently, my student sent me a recording he came across of my grandfather playing Chidori no Kyoku. Recordings of Kodo IV are rare so I was very excited to hear it. As I was listening, it occurred to me that I have audio of my great-grandfather, grandfather, and father, all playing the same piece. This presents me an interesting opportunity to dissect some of the ways our playing has changed over the years. At least as much as can be ascertained from the limits of a single sample*.

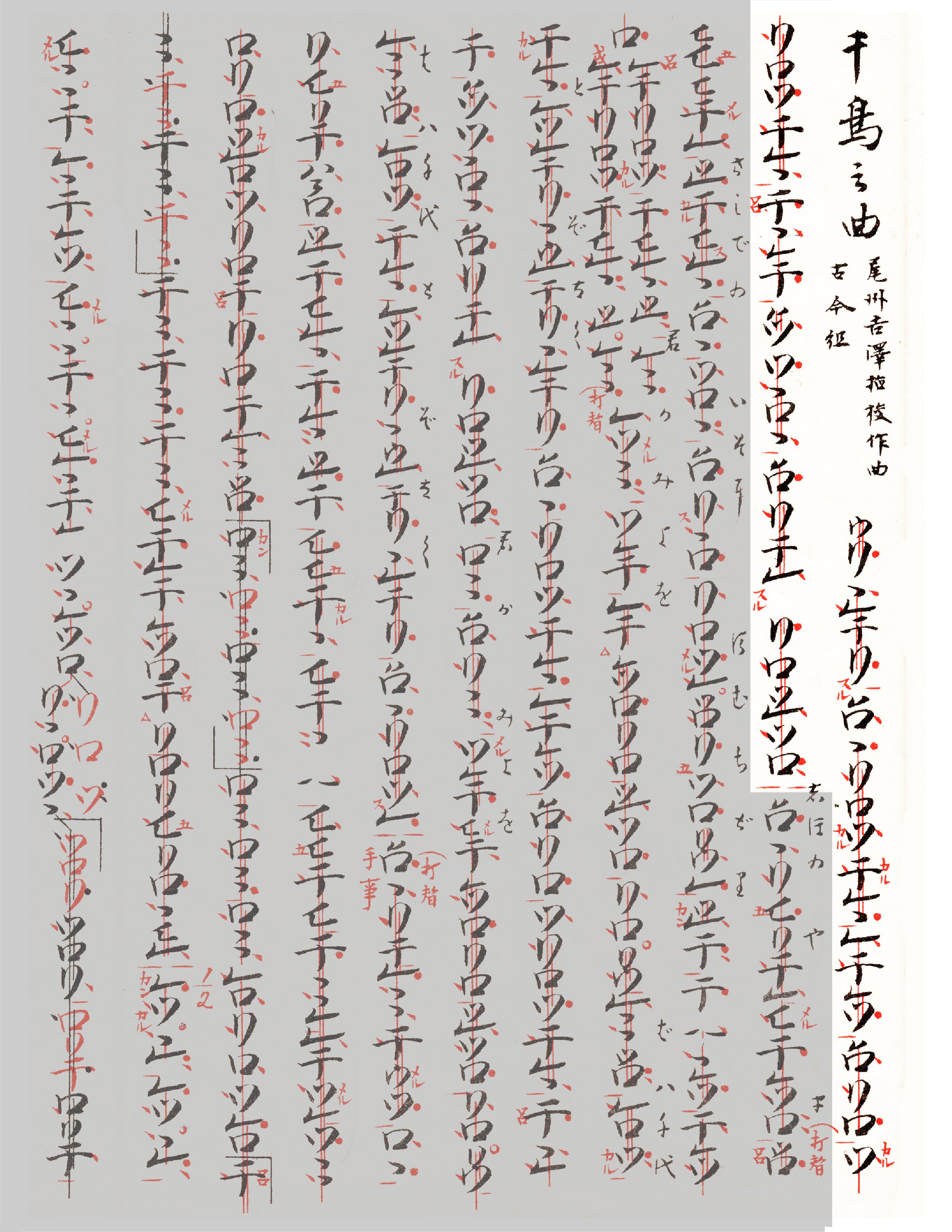

Chidori no Kyoku (Song of Plovers) is a 19th century sōkyoku (koto music) piece composed by Yoshizawa Kengyō in 1855 and features a then-new scale and mode called kokin-chōshi. The song is based on two poems from the 10th and 12th centuries.

For the purposes of demonstration, I’ll play the maebiki, or instrumental introduction, seen here in white:

I kind of wish I could make “follow the bouncing ball” -type videos you could follow along…

First up is Kodō III, recorded in 1930. Curiously, he recorded this solo without koto, despite this being a koto piece where shakuhachi would be considered accompaniment. It is accepted that the original composition was for koto and kokyū, a bowed Chinese instrument. Kodo III believed this piece could be played almost like honkyoku.

As always, when I listen to Kodo III, the first thing I’m struck by is the incredible power in his shakuhachi “voice.” Even in this excerpt, I hear what sounds to me like distant thunder; it’s like an undercurrent to every note.

His phrasing is unique in this instance as he is not confined by the koto or voice. Thus his expression is much freer.

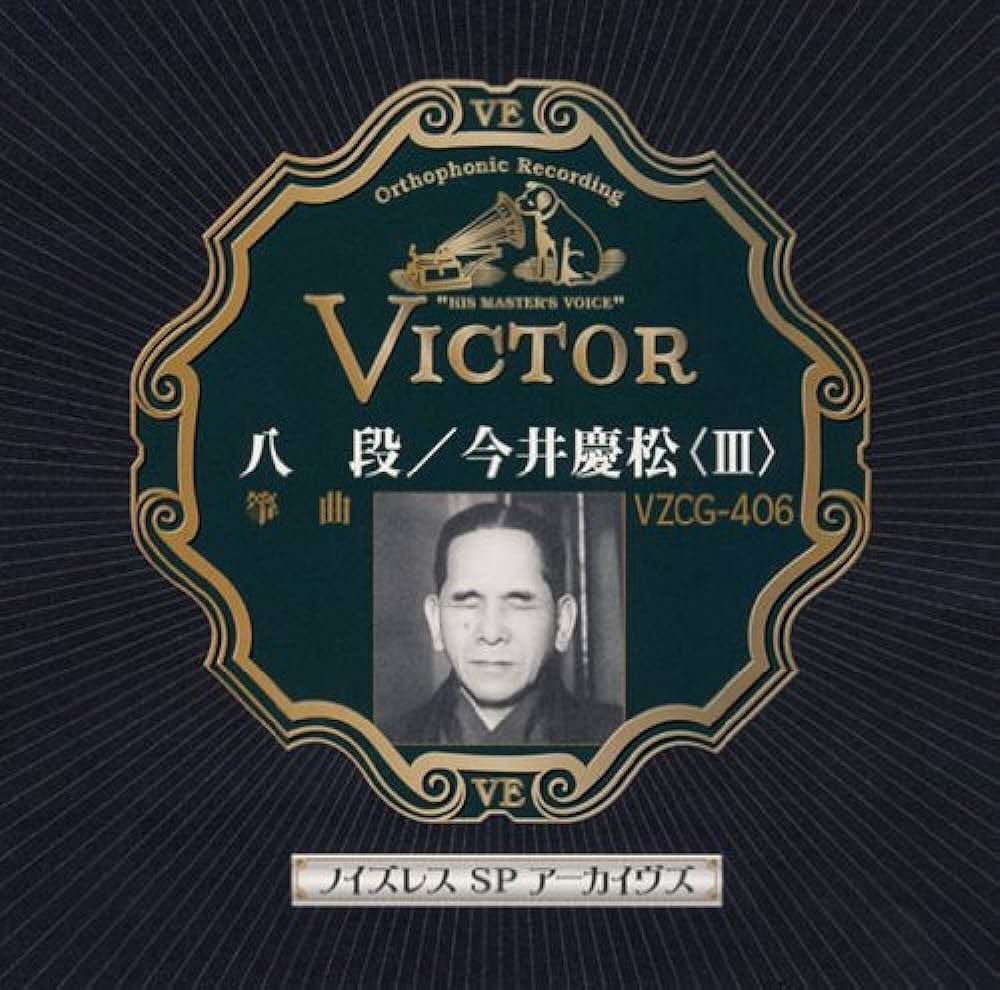

Kodo IV’s interpretation of the same piece is with koto great Imai Keishō.

Imai Keisho, far left

(image from Hachidan from the same collection)

As is often the case with older recordings, we have to allow for limitations of recording at 78 RPM. So, this particular performance is slightly rushed to accommodate for time. This would have been recorded live, obviously, and likely with one microphone. This means the artists have to mix themselves, being mindful of each other, dynamically.

I’m struck by the consistency of his playing. His tone is beautiful; present, but not overpowering. This is something I strive for in my own playing.

Next, we hear my father, Kodō V alongside one of my heroes, Tani Sumi. This recording is from an album he called Shakuhachi no Shinzui (“The Essence of Shakuhachi”), released in 1975. Given that it is the now standard LP speed of 33 ½ RPM, they are allowed a bit more expression.

My dad was always very terse with me, so I love reading the liner notes from this record, which are so contemplative. Of Chidori, he said:

This melody was the very first melody I performed on stage, an event that took place in January, 1950, when I performed together with a group of lovely girls who were studying under Shojuku Kojima. It also was my debut piece on television. Later on, I joined another teacher, Shinki Sato, but I still cherish this song in my heart, and although well over twenty years have gone by since, I still wish that I could return to that state of innocence I was in back in those days.

Finally, here’s me:

(apologies for my appearance but it’s freaking cold here)

In my case, Chidori was the third piece I learned after Kurokami, a classic shamisen piece, and Rokudan, one of the so-called danmono, or purely instrumental koto music. Thirteen years had passed between when my father played Chidori for his album and when he taught it to me. In that time, he refined many elements of his playing; most notably—to me, at least—the subtle pip! you often hear at the end of a phrase. This comes from lifting your fingers before you finish the note, and it was not something he tolerated in my playing.

By the time I was studying with him, he had also de-emphasized his use of suri—a kind of slur between descending notes—especially during sankyoku (ensemble) performances.

I’ve always felt there was a close resemblance between my great-grandfather and his son, and my father and me. This is not a sensational opinion, but I often remember how many people told me I resembled my grandfather both in manner and as a player, a man I never met. Before I heard his Chidori, I hadn’t heard the similarity, but my main takeaway from this exercise has been—possibly wishful thinking here—that we do sound more alike than I had previously been aware.

But those are my thoughts. Did anything occur to you listening to this four-generational span?

More anon,

Hanz

* I’ve often said that we shouldn’t rely too much on recordings, especially when it comes to traditional music. People bandy around words like “definitive” regarding certain recordings, but the goal in traditional music is not to perform the exact same way, every single time we play something. In fact, the beauty is often in the evolutionary nature of the music, with slight variations here and there. While those differences may be subtle, they are intrinsically part of the tradition. This music is meant to be heard live and in person, and no freeze-dried version of something can ever epitomize any given player.